The government's Future Homes consultation presents air-source heat pumps as a mass-market high-efficiency heating solution. However, field trial evidence shows that in...

Heat pumps are a possible way to close the gap between low-cost, high-carbon gas power and high-cost, low-carbon electricity in heating the British domestic sector. Energy Systems Catapult’s recent project tested the feasibility of installing them across the many home types and ages that comprise the British housing stock.

In December 2021, Energy Systems Catapult published their first reports of their Electrification of Heat demonstration project (EoH), which set out to show the potential for heat pumps in Britain by installing them in different types of home. The project was funded by the government’s Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (DBEIS) as part of the move toward a net-zero economy. With 85% of British homes dependent on gas for heating, replacing gas boilers with electric alternatives is an essential part of decarbonising the economy.

This is the first article of our two-part series on the project:

Electrification of Heat project 2: the Atamate view

At Atamate, we would like to congratulate Energy Systems Catapult on delivering a complex project and delivering information that will improve decisions around the role of heat pumps in Britain. However, we do have some concerns:

Here we describe our understanding of the EoH project and the outstanding points that we hope will be addressed in the future.

The EoH project’s objective was to install heat pumps in a ‘representative range of housing archetypes’. That is an important consideration for Britain, where the housing stock includes more homes built before 1919 than since 1990 with the majority dating to between 1919 and 1980 [PDF]. The age range of British housing stock inevitably leads to very different building designs even among buildings of a similar size and value.

With a chronic housing shortage and targets for building new homes being consistently missed, there is no realistic prospect for a large-scale replacement of existing homes so decarbonising the domestic sector will depend on renovating existing buildings. If heat pumps are to replace gas in British homes, they will need to be installed across the wide diversity of housing that makes up the British stock.

The EoH project succeeded in installing 742 heat pumps of four different types:

On the basis of those installations, Energy Systems Catapult declared the project a success and added case studies that described four of the installations in detail.

The background to the EoH project is a critical problem in the domestic sector’s transition to net-zero: generating electric energy emits far less greenhouse gas than burning natural gas, but a unit of electric energy is four to five times the cost of an equivalent unit of gas energy.

Currently, international gas prices are at a historic high and it is not clear whether they will return to their previous levels or the difference between gas and electricity will be narrower in the future. In either case, the current gas price shock highlights the domestic sector’s vulnerability to international price fluctuations and provides another reason to replace gas power with electricity, which can be generated renewably within Britain.

Heat pumps have been widely promoted as the solution to the price gap because they augment the energy drawn from mains electricity with heat energy extracted from the environment. The government’s Climate Change Committee (CCC) suggested them as a mass-market solution for decarbonising the domestic sector in a 2019 report. Based partly on that report, they featured prominently in the 2019-2020 Future Homes consultation on revisions to the building regulations relating to conservation of heat and power, which are expected to come into force in the next few years.

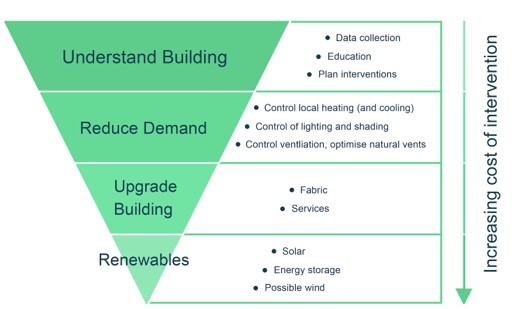

At Atamate, our view is that heat pumps are one solution among many that a designer can choose from, and we are concerned that they are often presented as a panacea for the problem of delivering low-carbon energy. Our preferred approach is based on what we call the Atamate energy hierarchy. The first step is to understand the building by collecting data, and to use that data to assess how best to spend money to improve its energy efficiency. Our white paper on renovating an existing building to achieve net-zero [PDF] describes our approach in more detail.

|

|

The Atamate energy hierarchy |

When any technological solution is over-emphasised, there is a danger that other options are excluded from consideration. In our assessment of the Greater London Authority’s modelling study of heat pumps in London [PDF], we showed why that matters. The conclusion that heat pumps were the best solution to the problem presented was not supported by the data.

We expect that there are situations in which a heat pump will emerge as the best solution, mostly to replace gas as a power source for central heating in existing homes. However, installing a heat pump is a major upgrade incurring substantial capital costs, which should only be considered if the data shows it is the best option in terms of cost and carbon efficiency.

We have similar reservations around Energy Systems Catapult’s announcement of success, which we will discuss in detail in the next post.

If you’d like to know more about how atBOS controls can make the most of a heat pump, ask us on the form below and we'll be happy to discuss it.

The government's Future Homes consultation presents air-source heat pumps as a mass-market high-efficiency heating solution. However, field trial evidence shows that in...

Energy Systems Catapult has declared its Electrification of Heat (EoH) project successful in installing heat pumps in all types and ages of British homes. However, their...