Britain faces the dual crises of a serious housing shortage and a construction industry that's losing skilled workers faster than it recruits them. Offsite construction...

A range of modern methods of construction (MMC) is revolutionising the construction industry. Many involve work being done in factories rather than building sites, hence the term 'offsite construction'. Here we give an overview of the types of offsite construction and the techniques behind them.

This post is part of our series on offsite construction techniques. The others are:

Offsite construction: advantages in costs and efficiency

Constraints to offsite construction in Britain

Can offsite construction solve Britain's housing crisis?

When construction and modern industry first met

When construction and modern industry first metIt all started with bananas.

The concept of building all or part of a structure offsite goes back at least as far as the Romans, whose military engineers worked to similar specifications throughout their entire empire. The reproduction of the Lunt Fort near Coventry, on the site of the original which has been partially excavated, shows what the product of offsite construction looked like two millennia ago.

It was Joseph Paxton, chief gardener of Chatsworth House, who brought offsite construction into the industrial age. He started by building greenhouses and graduated to conservatories which he used for his botanical experiments. Perhaps his most successful experiment was the one that led a particularly tasty strain of banana, which he named the Cavendish after his employer and the owner of Chatsworth House, William Cavendish, who was also known as the 6th Duke of Devonshire and probably expected a few things to be named after him.

Paxton may have started as a horticulturalist but he acquired an impressive grasp of architecture while he was designing his conservatories. By the time the call for proposals for a building to house the 1851 Great Exhibition was sent out, Paxton was confident enough to submit one.

Paxton may have started as a horticulturalist but he acquired an impressive grasp of architecture while he was designing his conservatories. By the time the call for proposals for a building to house the 1851 Great Exhibition was sent out, Paxton was confident enough to submit one.

The committee planning the Great Exhibition had allowed an absurdly short period of time for preparation, which may have helped them get over any traditionalist prejudice against a design that looked suspiciously like a giant greenhouse. The building that would become world famous as the Crystal Palace allowed for the components to be fabricated at factories around the country and rapidly assembled in London's Hyde Park, which was a major selling point with the opening date rapidly approaching.

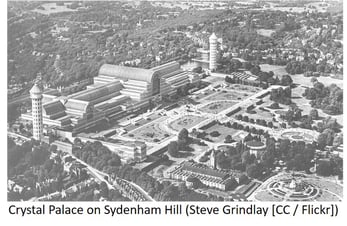

The doors of the Crystal Palace opened to the Great Exhibition opened only nine months after construction started. For context, it took more than 20 years to complete the Houses of Parliament, which were of a similar size and were under construction at the time the Crystal Palace was being built. Parliament was still under construction throughout the Great Exhibition and as the Crystal Palace was dismantled and rebuilt on Sydenham Hill, where it stood for more than 80 years and lent its name to a football team before being destroyed by a fire.

The story of the Crystal Palace demonstrates some of the key advantages of offsite construction that remain pertinent today: the components could be built wherever it made the most sense to build them, then transported to the construction site and assembled rapidly and to a predictable schedule.

Offsite construction has come a long way since Paxton's time. A recent example of what is now achievable was the 30-storey Ark Hotel which was constructed in Changsha, China in 15 days and is resistant to a Richter 9 earthquake - of which there have been less than 10 recorded since 1700:

And Paxton's bananas?

The Cavendish took the world banana trade by storm and is still the banana you're most likely to see on the shelf at your local supermarket.

Modern offsite construction can involve anything from assembling a few components in a factory to assembling an entire building  that's delivered to the site on a convoy of trucks. What it cannot do is completely replace onsite construction: even the building on those trucks will need some assembly onsite.

that's delivered to the site on a convoy of trucks. What it cannot do is completely replace onsite construction: even the building on those trucks will need some assembly onsite.

Offsite construction is not a single technique but a whole range of methods that can be used to move as much or as little of a building project off the building site and into a factory as makes sense for that project.

According to a guide by Modularize, who offer design and development services in the field of offsite construction, offsite manufacturing systems can be broken down into four broad categories [PDF]:

Any part of a building made in a factory and brought to the construction site can be classed as a sub-assembly, which forms part of a component system. Sub-assemblies can be as small as locks and handles for the doors, or they can be larger components such as pre-assembled roof trusses. Sub-assemblies are likely to be used in a construction project that predominantly uses onsite techniques, but enables some of the trickier components to be built in a factory that allows for more precision than the building site.

Panelised systems are components that can be flatpacked, rather like an Ikea wardrobe that’s grown up into a full-sized building. Parts of the walls, ceiling or roof can be constructed in a factory and assembled on site. The above video shows such panels being fitted into place to form the Ark Hotel's exterior.

The panels can be built with mechanical and electrical services, such as electrical sockets and water feed pipes, already in place. They still need to be connected as the building is assembled, but having them built in saves onsite installation time.

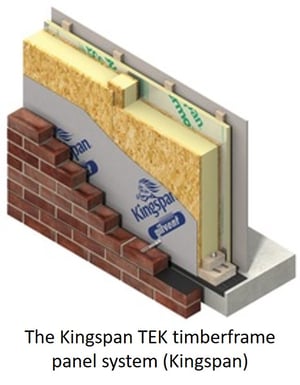

There are various designs used for the panels themselves. For example, the Kingspan TEK system uses a type of structurally insulated panel (SIP) that sandwiches urethane insulation between two timber panels. The system is well-insulated and airtight, which ensures the building’s energy efficient, but also simple enough to be adapted to the walls, roofs and floors, and to be adapted to the buildings designed by construction firms like Bentley SIP Systems.

There are various designs used for the panels themselves. For example, the Kingspan TEK system uses a type of structurally insulated panel (SIP) that sandwiches urethane insulation between two timber panels. The system is well-insulated and airtight, which ensures the building’s energy efficient, but also simple enough to be adapted to the walls, roofs and floors, and to be adapted to the buildings designed by construction firms like Bentley SIP Systems.

Another option is the ceramic composite paneling largely made out of recycled glass, which are being pioneered by Tufeco and are based on materials developed for the aerospace industry. Tufeco claim that their panels are much faster to produce than other designs on the market, and that the basic design can be easily adapted to bespoke building designs.

Volumetric systems involve at least partial assembly of the panels into rooms before they leave the factory. The advantage is that the units can simply be manoeuvred into place with a crane once they arrive at the construction site. The disadvantage is that a volumetric takes up far more space on the back of a lorry than the panels it’s built from, so a vehicle that could deliver many rooms in panelised form might only be able to deliver one in volumetric form. The time savings onsite need to be substantial for volumetric systems to be chosen over panelised.

Some developments combine volumetric with panelised systems by incorporating kitchen or bathroom pods into buildings otherwise constructed using panelised or more traditional approaches. Because kitchens and bathrooms are the most technically complicated parts of many developments, it can be worth building them in a factory and transporting them even when it's not worth transporting other parts of the building.

A bathroom pod can be constructed in a building with the bath, toilet and tiling design of the client's choice, then transported to the site on the back of a lorry and simply plugged in.

A building that incorporates many identical substructures, such as a block of flats or a school, may be a suitable candidate for a modular design. Rather than simply building  the kitchens and bathrooms as volumetric units, the design divides the entire building into pods that are small enough to be carried on the back of a lorry. Because a large residential building involves large numbers of units built to a small number of designs, they can be mass produced in a factory far more efficiently than onsite, which offsets transport costs that are higher than if panelised construction had been used.

the kitchens and bathrooms as volumetric units, the design divides the entire building into pods that are small enough to be carried on the back of a lorry. Because a large residential building involves large numbers of units built to a small number of designs, they can be mass produced in a factory far more efficiently than onsite, which offsets transport costs that are higher than if panelised construction had been used.

Examples of modular buildings in the UK include the 249-flat Creekside Wharf [PDF] development in Greenwich or the 700-bedroom Victoria Hall student accommodation in Wolverhampton, both of which were built much quicker than would have been possible by any other means.

Britain is home to the largest modular building factory in the world, owned by Legal and General and sited in Sherburn, Yorkshire, which they claim has the capacity to produce 3,000 homes per year.

In the UK, modular construction has mainly been used for residential developments, but it can be used for hotels, schools, office blocks or any other type of development in which many elements are repeated. It's less useful for developments in which different buildings have different requirements, as incorporating bespoke components impacts the economies of scale that make modular construction cost-effective.

While modular construction is often presented as the technical cutting edge, there are innovations that are just beginning to progress from the stage of technology demonstration to application, and are likely to become more widely used in the coming years.

It's often said that a modern factory is run by a man and a dog. The man's job is to feed the dog. The dog's job is to bite the man if he fiddles with the machines.

It's a joke - for now - but it does reflect the fact that modern manufacturing is done largely by robots that can be left to get on with it unless a design parameter changes. As offsite construction moves building from the house to the factory, the process of manufacture will inevitably follow the car and aircraft industries and become progressively more automated. A short film showing Laing O'Rourke's offsite manufacturing facilities at the Explore Industrial Park, Nottinghamshire, shows that much of their process is already automated:

The robots are already beginning to escape from the factory and perhaps unsurprisingly, they're at their most frisky in Japan. The construction firm Komatsu has been collaborating with tech firm Skycatch on a system in which robot vehicles will be guided around a site using a map produced by drones hovering overhead. Komatsu has experimented with robotic vehicles before, but autonomous vehicles were never able to navigate the constantly shifting landscape of a construction site. Their solution was to strip the individual vehicles of their autonomy and hand control to a single artificial intelligence that integrates information from the drones and uses it to control the vehicles.

Komatsu developed their system to build stadiums for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, which involves developments large enough to have a number of works vehicles operating on them. It doesn’t look like it's ready to replace the humans working on the sort of development that puts up a single house, although it's a safe bet that Skycatch are working on it. As they do, it's safe to assume that they'll bear in mind that standardised of prefabricated components will suit the limitations of a robot.

Komatsu developed their system to build stadiums for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, which involves developments large enough to have a number of works vehicles operating on them. It doesn’t look like it's ready to replace the humans working on the sort of development that puts up a single house, although it's a safe bet that Skycatch are working on it. As they do, it's safe to assume that they'll bear in mind that standardised of prefabricated components will suit the limitations of a robot.

The Robotics & Crane based Automated Construction System [PDF] developed by Korea University's School of Electrical Engineering brings a degree of autonomy to the sort of crane that is typically used in high-rise construction, although its designers acknowledge that the type of construction it can handle is limited. It does point the way to the possibility that a given design for a modular building could be associated with a particular design for an autonomous crane designed for it.

One firm is committed to bringing the robots to Britain: Tufeco, who pioneered the panelised system using ceramic composites, state that they 'are fully committed to being able to build all of their schools, houses and commercial buildings, using fast build electric eco robots well by 2020'. If they can deliver on that commitment, they will be the first in Britain but they will not be the last.

In 2013, the Chinese firm Winsun printed the components for ten houses in their factory and assembled them onsite. The houses were built from what they describe as a 'special ink made of cement, sand and fibre, together with a proprietary additive' in their case report [PDF], although their CEO, Ma Yihe, mentions using recycled mine tailings in his own description:

Impressive as it is to be able to print ten houses in a day, the houses are small and very basic in their design, and the project was primarily intended to demonstrate the technology. Winsun went on to print the so-called office of the future, using a six-metre tall printer which was then shipped and assembled in Dubai. In an interview with the South China Morning Post, Yihe floated the possibility of a more flamboyant international client:

Donald Trump could build his wall much cheaper and in less than a year … We could definitely do it. Maybe at around 60 per cent of the projected cost and three to four times faster.

Like most people discussing Trump's wall dreams, Yihe was unable to keep a straight face. The interviewer describes him as laughing as he said it, 'although … not joking'.

Winsun use 3D printing for a panelised system of offsite construction, but the American startup Apis Cor went a step further when they printed a house onsite in less than a day:

Apis Cor claim that as well as being fast, their system can be programmed to any design that architects and engineers can come up with and make the point that printing the house as a single structure avoids the thermal bridges between different structural components that plague traditional design. Good insulation and airtightness is evidently a priority for Apis Cor, as their test house was built near Moscow in the depths of winter and their website refers to a project to build a human habitat on Mars.

As 3D printing technology stands, it's limited in that it has to use some form of concrete as a material. If 3D printing becomes as big as its proponents claim it will, we'll need to brace ourselves for a new wave of brutalist architecture. That doesn't mean we'll all want to live in a concrete home and forget about anything else a building can be made of, so 3D printing won't be sweeping away all other forms of construction any time soon.

It's likely to be a while before Apis Cor can scale their system up to the size of a supermarket or a tower block, so Winsun's approach of using 3D printing as an offsite construction method looks likely to have the most immediately realisable potential.

We've come a long way since Joseph Paxton's bananas.

Britain faces the dual crises of a serious housing shortage and a construction industry that's losing skilled workers faster than it recruits them. Offsite construction...

The British construction industry has been slow to adopt offsite techniques in spite of the savings in time and money they offer to developers when compared to...