The government's Future Homes consultation presents air-source heat pumps as a mass-market high-efficiency heating solution. However, field trial evidence shows that in...

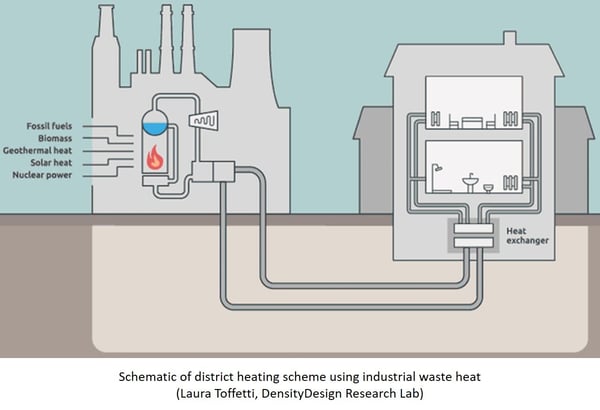

District heating schemes use a single powerplant to provide heating and hot water to many buildings. They have been promoted as important in decarbonising the British economy but their dependence on gas limits their carbon efficiency and heat is lost as it is distributed which causes internal gains.

District heating schemes, sometimes called heat networks, use a single powerplant to heat water which is piped around different buildings, supplying heating through radiators or underfloor heating as well as domestic hot water. Most systems currently installed in the UK use a gas-powered combined heat and power system (CHP) which also generates electricity.

We acknowledge that in a block of flats or a housing estate, a single CHP is often more efficient and requires less maintenance than a gas-powered boiler in every flat or house. In recent years, combined cooling, heat and power systems (CCHP) have become available which can pump cold as well as hot water, which can cool buildings during the summer as well as heating them in winter.

Further, the CHP can be replaced with systems of energy generation that work best on a medium scale. The UK government's Committee for Climate Change (CCC) estimated that the most energy-efficient sources for district heat [PDF] were either waste heat from factories, power stations or refuse incinerators, none of which lend themselves to the small scale of a single home or to being scaled up to be comparable with the power stations that supply the national grid.

The CCC saw the main use of district heating schemes as being in the non-residential sector and anticipated that only 12% of domestic heat would be supplied by district heating by 2050.

The CCC saw the main use of district heating schemes as being in the non-residential sector and anticipated that only 12% of domestic heat would be supplied by district heating by 2050.

In their recent Future Homes document, which is under consultation at the time of writing, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) take a different view. In their proposals for decarbonising the residential sector, MHCLG regard district heating as 'an important part of our plan in the future of low carbon heat, in particular in cities and high-density areas' (Section 2.12) which implies a much larger role for district heating than was suggested by the CCC report that MHCLG quote to support their view.

In an earlier post, We have discussed our concern that Future Homes tends to emphasise certain technologies over the intended outcome of cutting carbon emissions, and our view is that district heating is a case in point. There are several reasons to question whether district heating schemes are the most energy-efficient option for homes built or renovated for the coming decades.

The CHP systems that power most district heating schemes are powered by natural gas, which has been more carbon-efficient than electrical power in the past. However, recent years have seen the national grid shifting from coal to renewable sources. The carbon efficiency of mains electricity is now similar to that of mains gas and continues to rise, which means that natural gas is no longer the carbon-efficient option for a plant intended to operate years or decades into the future.

As the carbon efficiency of electricity continues to improve, natural gas is no longer carries the lowest environmental impact for a project intended to operate years or decades into the future.

As the carbon efficiency of electricity continues to improve, natural gas is no longer carries the lowest environmental impact for a project intended to operate years or decades into the future.

Maintenance presents a further problem with a district heating system: a CHP plant is complex enough to need a significant amount of maintenance and because it's more complex than a boiler, is more prone to a complete breakdown. Unlike the breakdown of a single boiler, the breakdown of a CHP system will leave every building it serves without heating or hot water.

Another maintenance consideration is that a single CHP system serves many heat interface units, each of which requires its own maintenance.

Another concern is raised by the competitive nature of the UK energy market, with different suppliers offering different tariffs that allow an individual to choose what is most efficient for them. The option to change supplier is lost if heating and power are supplied by district heating as each recipient of the plant's power is effectively locked into the supplier selected by the plant's management.

However the central plant is powered, there are inefficiencies inherent to district heating, partly because it can only provide space heating through 'wet' heating systems like radiators and underfloor heating and partly because hot water must be piped to the homes it services and partly because wet heating is rarely an efficient choice for a well-insulated building. Radiators take time to  warm up and more time to cool down, making them likely to heat a room to above the thermostat temperature. The occupants often respond by engaging the ventilation or opening windows, leading to an inefficient tug-of-war between the heating and cooling mechanisms while the temperature fluctuates between being uncomfortably hot and uncomfortably cold.

warm up and more time to cool down, making them likely to heat a room to above the thermostat temperature. The occupants often respond by engaging the ventilation or opening windows, leading to an inefficient tug-of-war between the heating and cooling mechanisms while the temperature fluctuates between being uncomfortably hot and uncomfortably cold.

In fact, modern well-insulated buildings need so little energy to heat that their largest expenditure is on heating water, which is something else that district heating can provide. However, hot water must be piped from the central plant to where it is needed and the building regulations that cover hot water (Part G) state that it must come out of the tap at no less than 48°C (118°F). At such high temperatures, energy is lost to the same laws of thermodynamics that underpin wet heating systems: a pipe full of hot water will conduct heat energy to the air around it. If the air around it is inside a room that is already at a comfortable temperature, a pipe full of hot water is likely to heat it to an uncomfortable temperature.

There are solutions to the problem of heat loss from circulating hot water. The distribution system can be designed with as much of the length of the pipe outside the building as possible to prevent heat losses overheating the building. Another approach is extremely good insulation for the pipes, although any insulation deteriorates over time and requires regular maintenance.

A more recent innovation in the domestic sector is used by systems such as the Zeroth energy system. Instead of heating the water to the temperatures at which it is used, Zeroth distributes water at 25°C (77°F) into a heat pump in e

ach flat which then heats the water to the desired temperature. By partially heating the water, the central heating system cuts the energy needed for the heat pumps in each flat. By not heating the water above the comfort temperature, it limits capital and maintenance costs by allowing the use of relatively cheap plastic pipes that do not need extensive insulation.

As with a CCHP plant, Zeroth can be used to distribute cold water in the summer, which cools a building more efficiently than mechanical aircon.

Distributed heating systems like Zeroth may work in situations where the efficiency advantages of a central plant are otherwise outweighed by the inefficiencies of distribution and may allow district heating to be extended further into the domestic sector than the 12% envisaged by the CCC. However, the main use of district heating is likely in commercial districts, where shops and office blocks concentrate their hot water requirements into a small number of centralised kitchens and bathrooms.

Our view is that district heating is only ever going to be the most energy-efficient option for a small part of the domestic sector, which does not justify the emphasis that MHCLG places on it in the Future Homes consultation.

If you’d like to know more about our views on the future of housing in Britain or on how our building controls can help to limit overheating, ask us on the form and we'll be happy to let you know.

The government's Future Homes consultation presents air-source heat pumps as a mass-market high-efficiency heating solution. However, field trial evidence shows that in...