Heat pumps are a possible way to close the gap between low-cost, high-carbon gas power and high-cost, low-carbon electricity in heating the British domestic sector....

This winter’s hike in international natural gas prices will lead to heating price hikes this winter. It exposes the vulnerability of Britain’s dependence on imported gas, both for heating homes and for generating electricity, and illustrates the importance of initiatives to replace gas heating systems.

If you live anywhere between Shetland and the Scilly Isles, it won’t have escaped your notice that Britain is currently experiencing an energy price shock. The cause of the crisis is that the wholesale price of natural gas on the international market has been rising. It doubled between February and July of this year which is when price rise turned into price shock, doubling again by mid-September. It’s already sent several energy suppliers to the wall and has placed a massive financial burden on industrial customers who buy gas at wholesale prices.

Domestic customers have been protected from the worst of the shock because retail prices are capped by the energy regulator, Ofgem, and are currently set at 4p/kWh for natural gas and 21p/kWh for electricity for a typical customer. In the past, energy suppliers have set their prices below the cap to try to attract new customers but now that the wholesale price hike obliges suppliers to sell gas at a loss, they are incentivised to set the gas price at the cap although there may be more room to compete on electricity prices.

We’re in for an expensive winter and it’s likely to get worse next year; Ofgem will revise the cap in March 2022 and, according to the Dutch bank BN Amro, gas prices are unlikely to normalise before 2023. We should be prepared for the cap to rise and prices to follow.

Right now, Britain’s dependence on natural gas is hitting us all in the wallet but it also serves as a wake-up call for another issue bearing down on the domestic sector. The government’s Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities (DLUHC) - formerly the Ministry for Housing, Communities & Local Government (MHCLG) - has stated the goal of making all newly built homes ‘zero-carbon ready’ by 2025. That means that no gas boilers will be installed in new homes and the government hopes that no new gas boilers will be installed at all after 2035 as existing buildings transition from mains gas to mains electricity.

The intent behind transitioning from gas to electricity was to cut greenhouse gas emissions as part of the transition to a net-zero carbon economy by 2050. However, the current price shock has stress-tested the British energy market and revealed another reason: dependence on gas power leaves billpayers vulnerable to this sort of fluctuation in the global gas market.

In the past, the fundamental problem with the transition is that electricity is more expensive than gas. As Ofgem’s caps reflect, £1 of mains gas delivers around five times as much electricity as £1 of electricity. Converting a home from gas to electricity by simply ripping out the gas boiler and replacing it with an electric replacement will lead to financially crippling bills, so the conversion needs to be accompanied by measures that will cut the overall energy demand.

The current price shock will push up the price of gas but it is unlikely to place it on a par with electricity for any length of time, so it has not resolved the conversion problem. It has simply created an entirely new pricing problem.

The current price shock will push up the price of gas but it is unlikely to place it on a par with electricity for any length of time, so it has not resolved the conversion problem. It has simply created an entirely new pricing problem.

To understand where we are and how we ended up here, it helps to understand where our energy comes from.

Britain’s North Sea gasfields allow National Grid to source some natural gas domestically but two trends of the early 2000s left Britain dependent on gas imports:

Britain wasn’t alone in moving from coal to gas and in China, a recent coal shortage has increased gas demand in the world’s second largest economy. Norway, one of the world’s major exporters, has increased their export volume but Gazprom, Russia’s main supplier to Europe, has not. The simultaneous increase in demand and fall in supply has inevitably led to a rise in prices.

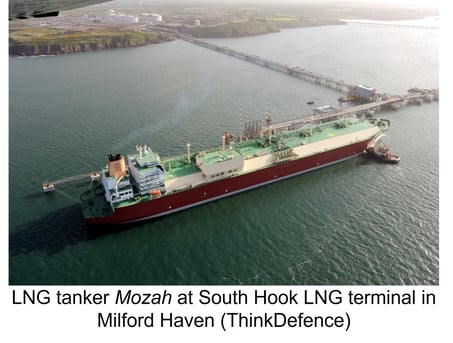

With 85% of British homes using mains gas for heating [PDF] and, according to the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy’s (DBEIS) latest energy report, nearly half of Britain’s gas imported by liquid natural gas (LNG) tankers, there was no escaping the impact of price hikes.

Further, Britain’s last large-scale gas storage facility was decommissioned in 2018. Gas storage had been a lucrative business when prices were significantly lower in the summer than in the winter but when prices levelled out, gas storage could no longer be run at a profit. At the time, representatives from the energy industry asked the government to step in with Chris Moffatt of the consultancy Moffatt Associates warning of, “complacency in the government that…the best course of action is to just accept these price shocks”.

The government did not change its position that storage should be left to the market, effectively dismissing the idea that gas storage should be part of the national infrastructure. Storage would not have insulated Britain from international price fluctuations but countries like Germany, which has seventeen times the British gas storage capacity, at least have a buffer against the price shocks that Moffatt warned of. Britain is left dependent on a constant flow of LNG tankers at whatever price the international market dictates.

Rises in gas prices tend to cause rises in electricity prices simply because much of the British electricity grid depends on gas to power it:

Sources of electricity generation by fuel type in the UK in 2019:

|

Fuel type |

Total energy (TWh) |

Proportion of total (%) |

|

Coal |

7.0 |

2% |

|

Oil & other |

9.2 |

3% |

|

Gas |

131.9 |

41% |

|

Nuclear |

56.2 |

17% |

|

Hydro |

5.8 |

2% |

|

Wind & solar |

76.4 |

24% |

|

Other renewables |

37.3 |

12% |

|

Total |

323.8 |

|

DBEIS (2021) UK Energy in Brief 2021 [PDF]

Wind and solar remain the major source of renewable energy and although they only account for around a quarter of electricity generation at present, they have expanded rapidly from less than 1TWh between them in 2000 [PDF], amounting to an increase in capacity of over eighty times by 2019.

The early 2000s saw the beginning of a reorganisation of electricity generation as the grid moved away from coal and toward wind and solar power. Wind and solar deliver low-cost electricity without emitting greenhouse gas but they are dependent on the elements; solar panels don’t produce power at night and wind turbines don’t produce power when the wind doesn’t blow. With no efficient way to store electricity, wind and solar power need to be backed up with ‘firm’ generation methods whose capacities can be directly controlled to make up the difference.

That’s where gas comes in. It’s more carbon-efficient than coal and - at least until the current price shock - it’s been cheaper:

Costs of electricity generation by various fuels before the 2021 gas price hike.

|

Generation source |

Cost (£ / MWh) |

|

Coal1 |

134 |

|

Nuclear1 |

93 |

|

Natural gas2 |

85 |

|

Offshore wind2 |

57 |

|

Onshore wind2 |

46 |

|

Large-scale solar2 |

44 |

1DBEIS (2016) Electricity Generation Costs Table 16 [PDF]

2DBEIS (2020) Electricity Generation Costs 2020 Table 4.17 [PDF]

From the perspective of electricity generation, early September was a particularly bad time for gas prices to take flight because the electricity grid was leaning on its firm generation more than usual. Many power stations were still closed for maintenance, which is usually scheduled for the summer when demand is low, but the first two weeks of September saw the lowest wind speeds for several years.

The British grid does not stand completely alone; undersea cables called interconnectors allow electricity to be traded with the national grids of France, Belgium, Holland and Ireland. Interconnectors allow trade that takes advantage of differing prices between neighbouring countries as well as allowing them to back up each other’s national grids when one of them hits the sort of bad patch that beset Britain in early September. It would have been a particularly inopportune time for an interconnector to fail but Murphy’s remains the one unbreakable law of infrastructural management. A substation of one of the two interconnectors linking the British and French grids caught fire, causing enough damage that it will not be back to full capacity before May 2023.

The series of unfortunate events left the electricity grid more than usually dependent on gas just as gas prices were soaring but while gas prices show no sign of coming down, the problems with electricity generation have largely been resolved. The wind is blowing again, the power stations closed for summer maintenance are mostly back online and a new interconnector with Norway was completed at the beginning of October and is scheduled to be up to full capacity by the end of the year.

None of that will allow the national electricity grid to function without at least some input from gas-fired power stations so the gas price hike is bound to lead to some increase in electricity prices. The size of that increase remains to be seen.

We may be wise to regard the gas price shock as a wake-up call. The national grid is in the process of transition from high-cost, high-carbon coal to low-cost, low-carbon renewable electricity and is currently dependent on gas as a mid-cost, mid-carbon interim measure. Unlike either coal or renewables, gas needs to be imported which places Britain at the whim of international gas prices.

Britain was one of the first countries to make that transition but others are following the same trajectory, which is likely to increase the international demand for gas. The current price shock is likely to be temporary, if long enough to be painful, but we cannot expect the wholesale price to remain stable at the level we’ve grown used to over the last 20 years. The sooner Britain completes the transition from gas power to renewables, the sooner we will be protected against price shocks.

Britain was one of the first countries to make that transition but others are following the same trajectory, which is likely to increase the international demand for gas. The current price shock is likely to be temporary, if long enough to be painful, but we cannot expect the wholesale price to remain stable at the level we’ve grown used to over the last 20 years. The sooner Britain completes the transition from gas power to renewables, the sooner we will be protected against price shocks.

As Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist at the Breakthrough Institute explained to the BBC World Service’s Inquiry:

The UK is a glimpse into the future that the rest of us hope to experience with some changes…A lot of us are very focused on how the UK can push through the harder parts of reducing its emissions now that a lot of the easy work has been done… If we had started planning a little ahead of time…we wouldn’t be quite as dependent on [gas] as we are today and we wouldn’t be quite as subject to…these extremely high prices we’re seeing right now.

Hindsight for Britain is foresight for the rest of the world.

That’s cold comfort as we look forward to an expensive winter while the economy is still reeling from the covid-19 pandemic in which more than one household in ten is classed as being in fuel poverty [PDF], meaning that the cost of adequately heating the home would leave its occupants below the poverty line.

Possible shorter-term solutions will depend on what is available for a given household. Anyone who lives in a house with a solid fuel burner would be well advised to gather up any scrap wood they can get their hands on. Anyone working from home, who needs most of their heat in a single room, might consider a 200-300W infra-red heater, which requires considerably less energy than a boiler rated in the kilowatt range and uses it substantially more efficiently than fan or panel heaters.

For most of us, it’s going to mean several months of piling on the jumpers.

If you’d like to know more about how the atBOS platform can enhance the energy performance of a home or any other type of building, ask us on the form and we'll be happy to discuss it or download our Net Zero whitepaper now:

Heat pumps are a possible way to close the gap between low-cost, high-carbon gas power and high-cost, low-carbon electricity in heating the British domestic sector....

There are many innovations transforming building services driven mainly by the huge challenge of achieving Net Zero targets. In a series of articles, we look at these...