The 200 common cold viruses are more prevalent in the British winter. That's mainly because indoor relative humidity drops below the comfort threshold of 40%, making it...

The urban environment facilitates respiratory virus transmission. COVID-19 is now the major threat but the common cold has long had a serious impact on wellbeing, personal income and the economy. The factors by which urban living aids virus transmission are known but little attempt has been made to address them.

This article is part of a series on viruses in the built environment, which is a companion to the article on the suite of applications that Atamate is developing to mitigate their effects.

Viruses indoors 2: Licht und Luft

Viruses indoors 3: Introducing the common cold

Viruses indoors 4: the flu season

Viruses indoors 5: The winter vomiting bug

In a year that has been dominated by one respiratory virus, asking why respiratory viruses are important may seem like asking a silly question. COVID-19 has arrived on the scene like a wrecking ball, forcing choices between draconian and economically destructive policies to control it or allowing it to kill one in every 100-200 of us and leave countless others ill for weeks or months at a time. In the UK, it killed 40,000 people in the three months between mid-March and mid-June 2020 which, for context, is roughly as many as were killed by the 1940-1942 blitz over eighteen months of intensive bombing.

Yet the problem of respiratory viruses did not begin with COVID-19. We're so used to being plagued by colds that we tend to forget that respiratory viruses have always been a significant problem and will continue to be a significant problem when the worst of the current pandemic has passed.

For most of us, a cold is a minor inconvenience but a virus that causes a cold in a healthy person can cause a serious disease in someone more vulnerable, either because they have underlying health problems or simply because they are elderly. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, The European Centre for Disease Control estimated that the most dangerous of the respiratory viruses, influenza, cuts  more lives short across Europe than any other infectious disease. Even if we succeed in getting COVID-19 under control, influenza is not going to go away and neither are any of the other 200 common cold viruses.

more lives short across Europe than any other infectious disease. Even if we succeed in getting COVID-19 under control, influenza is not going to go away and neither are any of the other 200 common cold viruses.

Media reports on COVID-19 usually focus on the deaths it causes but as with most diseases, to focus on the death toll is to miss much of what is going on. It's becoming clear that even a case of COVID-19 classed as 'mild', meaning that the patient does not need to be hospitalised, can be damaging enough to leave that patient fatigued and impaired for weeks or months.

Similarly, we often dismiss the effect of a respiratory virus as 'only a cold' because there isn’t much we can do about it, but 'only a cold' can mean a significant impact on wellbeing. Colds leave us debilitated, fatigued, underperforming at work and missing out on social activities.

Colds also have a significant economic impact. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) consistently ranks 'minor illnesses' as the largest cause of sickness absence from work. The ONS didn't quantify how much 'minor illness' is caused by the common cold which was in the same category as migraines, stomach bugs and various other afflictions that we all get from time to time. A report by the consultancy FirstCare, titled Change at Work, dug a little deeper and identified the common cold as by far the most common minor illness.

The ONS attributes 27% of sick days in 2018 to minor illnesses so if we take the conservative estimate that three-quarters of the ONS's minor illnesses are colds, then around 20% of all sick days are caused by colds. The FirstCare estimated that sick days cost the pre-COVID-19 UK economy £18 billion per year so if colds were responsible for 20% of that, cold viruses were costing the economy be £3.6 billion per year which is around 15% of the UK's social services budget or more than Barclays Bank's net income for 2019 [PDF].

From an employer's perspective, colds are particularly disruptive because they're not evenly spread throughout the year but are more prevalent in the winter. A winter in which several colds spread through a workplace can lead to a business underperforming for several months due to employees either taking time off or coming to work too ill to function at their full capacity.

Such 'presenteeism', meaning people coming to work while ill, facilitates the spread of a cold virus so instead of having one employee absent or working from home, several employees will either take time off or become presentees themselves and split their work time between actually working and nursing their sniffle. According to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD)'s recent Health and Wellbeing at Work report, written immediately before the COVID-19 pandemic, presenteeism is commonplace in the UK and few employers take steps to discourage it.

Such 'presenteeism', meaning people coming to work while ill, facilitates the spread of a cold virus so instead of having one employee absent or working from home, several employees will either take time off or become presentees themselves and split their work time between actually working and nursing their sniffle. According to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD)'s recent Health and Wellbeing at Work report, written immediately before the COVID-19 pandemic, presenteeism is commonplace in the UK and few employers take steps to discourage it.

Encouraging employees who are ill to take time off to recover is unquestionably better for them but it may also limit the repeated disruption that colds can cause during winter.

Now that COVID-19 is with us for the foreseeable future, the practice of presenteeism is a danger to the health of employees. What appears to be a cold may actually be COVID-19 and while one person may have nothing worse than a sniffle for a few days, they may infect someone who will become seriously ill. It is also likely to disrupt the functioning of the business because even if no one becomes seriously ill, the business may need to be temporarily closed.

Colds cost productivity for employers which in turn leads to a loss of tax revenue that could be used to fund the over-stretched health service. Perhaps more importantly, a cold can cause a major loss of personal income to casually employed workers who do not get paid if they are too ill to work.

Respiratory viruses hit us in the workplace. It's time we asked what the workplace can do to make it less easy for them.

The influenza pandemics of 1957 and 1968 focused research interest on respiratory viruses at the same time that a lot of new virological techniques were being developed. Much of what we now know about respiratory viruses comes from that period.

Then fifty years passed without a respiratory pandemic so we lost interest and forgot what we'd learned.

Now that COVID-19 has rudely reminded us that we should have remembered our lessons, it's time to dust off a 1986 review of respiratory virus research led by Anthony Arundel who was then based at Simon Fraser University's Department of Computing Science, British Columbia, Canada. The Arundel review identified six factors that govern respiratory virus transmission in the indoor environment:

1. The number of infected people producing contaminated aerosols.

2. The number of susceptible individuals.

3. The length of time for which individuals are exposed.

4. The ventilation rate.

5. The settling rate of contaminated aerosols.

6. The survival of pathogens attached to aerosols.

If we tried to invent a way of living that maximises those factors, we'd probably come up with something that looks very similar to a modern urban lifestyle.

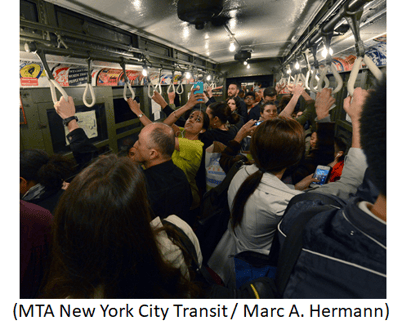

Let's take a day in the life of a suburban couple we'll call Paul and Sarah. In the morning, Paul drives their two children to school and then drives to work in an open-plan office where he mingles with his ![]()

colleagues. Sarah takes the commuter train to work at a college, where she spends her day giving lectures and running tutor groups. At the end of the day, the whole family return to their home.

colleagues. Sarah takes the commuter train to work at a college, where she spends her day giving lectures and running tutor groups. At the end of the day, the whole family return to their home.

Between Paul and Sarah's workplaces, Sarah's commute and the children's schoolday, they have been in contact with over a hundred people between them. Because their children move between classrooms and Sarah has used a train and lectured in two different lecture theatres, they have breathed the same air and touched the same surfaces as anyone carrying a cold virus who passed through those spaces before them.

Any cold virus that infects any of the family is likely to be passed around all of them and then, when all four of them are infected, they will be the ones breathing infected aerosols and contaminating surfaces that expose a hundred people a day. Not all of those people will be susceptible but with so many to choose from, it won’t need many to ensure the virus keeps circulating.

Comparing Paul and Sarah's day with the Arundel review's six points, we can see why the indoor environment is so conducive to virus transmission. It places us so close together that a virus breathed out by one infected individual has a good chance of finding its way to any susceptible individual nearby.

Worse, the indoor environment might have been designed to maximise the survival of viruses attached to aerosols or settled on surfaces. The great outdoors is not a friendly place for a virus waiting for a susceptible host for the following reasons:

We regulate our buildings and public transport for our comfort but in doing so, we shut out ultraviolet  light and we regulate the temperature to avoid the temperature extremes that the viruses find uncomfortable. Even the best ventilation systems don’t move air as quickly as a gentle breeze, which allows aerosols to linger in the spaces we occupy.

light and we regulate the temperature to avoid the temperature extremes that the viruses find uncomfortable. Even the best ventilation systems don’t move air as quickly as a gentle breeze, which allows aerosols to linger in the spaces we occupy.

If we wanted to design an indoor environment to facilitate the transmission of respiratory viruses, we wouldn't need to make any major changes.

We're all familiar with the consequences: annual outbreaks of coughing, sneezing and deliberating over whether to drag ourselves into work or not.

The next post in this series will describe what we can do about it.

If you’d like to know more about how Atamate Building Intelligence can support the wellbeing of the people who live and work in the urban environment, ask us on the form and we'll be happy to discuss it.

The 200 common cold viruses are more prevalent in the British winter. That's mainly because indoor relative humidity drops below the comfort threshold of 40%, making it...

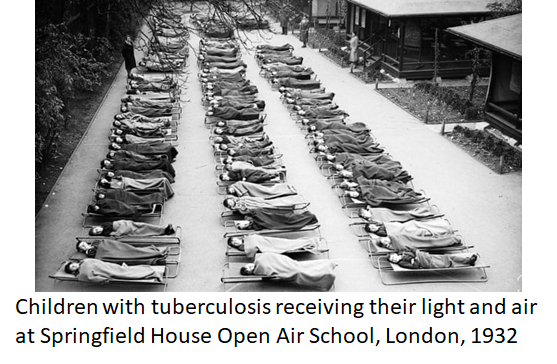

Modernist architecture in the early 20th century adopted the Licht und Luft principle, maximising light and ventilation to combat tuberculosis. Amid another airborne...